POPL VUH: Watercolors of Diego Rivera Bowers Museum, Santa Ana, CA December 12, 2015 – May 29, 2016

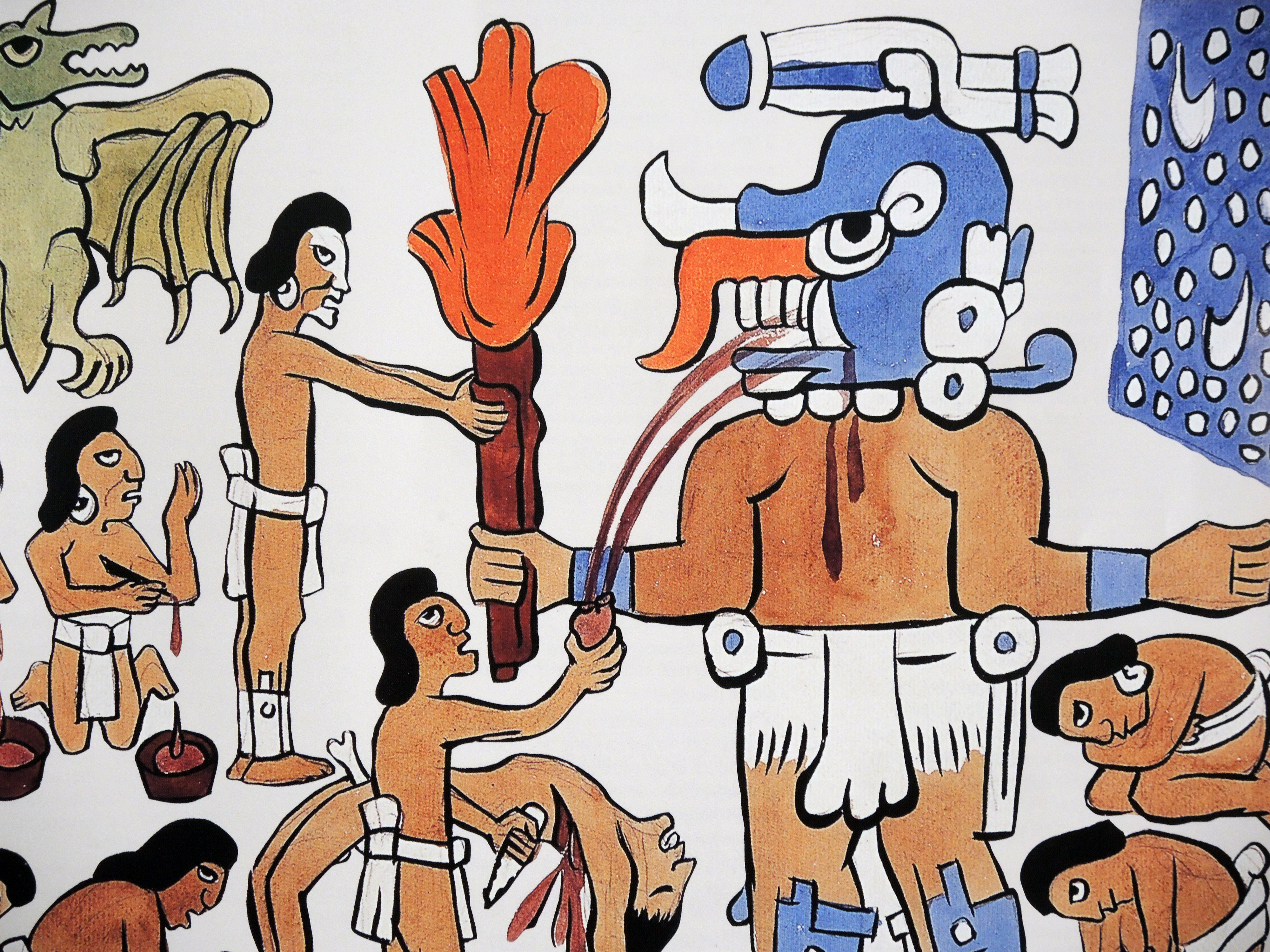

Diego Rivera (1886-1957), Human Sacrifice and Self-Sacrifice Before the God Tohil; illustration for Popol Vuh, ca. 1930, courtesy Bowers Museum, Santa Ana, CA

By clever design, the Bowers Museum has ‘hidden’ the installation of Diego Rivera’s watercolors of the mysterious Mayan story of Popl Vuh. You feel a bit like Indiana Jones with his torch trying to find the secret chamber of a jungle temple. After walking along a high-ceiling hall and passing down a long ramp flanked by ancient relics of dogs and tomb figures, you duck your head as you pass through a smallish (Mayan size?) doorway into the treasure room. Like beads in a necklace strung along the walls, Rivera’s richly painted watercolors depict the Gods and men of the Mayan world. The signs saying ‘No Photographs Permitted’ adds an unintended emphasis to the secret nature of these mysterious hieroglyphic images.

The cycle of creation and fertility myths called Pophl Vuh (translation: “Book of Council”) were first collected in a large text called a codex. Codices were richly illustrated, loosely bound books whose pages were made of bark paper. These sacred texts were passed down the centuries by the Lords and venerated scribes of the Quiché-Maya people, who lived in the Guatemala highlands of Central America from ca.1200 A.D. to ca.1520s A.D.

The first known modern text was prepared by Father Francsco Ximénez (1666-ca. 1729), a Dominican priest. He based his work on an earlier Latinized version of unknown origin, now lost. Ximénez was an exception among the priests, who were under orders to destroy the codices. This codex, whose parts were hidden in secret caches, barely survived the passage of time. It’s ragged chronology of repeated loss and discovery has itself become the stuff of legend.

Diego Rivera was commissioned to illustrate Popol Vuh by the American scholar, John Weatherwax, in 1930. The intent was create 24 watercolors and several drawings to illustrate his interpretation of the codex, which he titled Seven Times The Color of Fire. But Rivera’s early enthusiasm was diluted by other interests and the Great Depression deepened, limiting the risk any publisher would take with exotic materials. Of the finished watercolors 17 are on display in the Bowers show. (When not traveling, they can be seen at the Museo Casa Diego Rivera in Guanajuato, Mexico.)

Rivera’s flatly painted, childlike illustrations are based upon the stylized figures and designs found on Classic Mayan ceramics and stone carvings, like those on view in the outer rooms. We follow the chronology of the myths, as Rivera begins with the Forefathers, the chief gods, including Heart of Sky, Tepeu, Cucumatz and Quetzal Serpent. In what is a common creation myth throughout the world, the gods parceled light out the darkness, made earth manifest, and created man.

It’s not easy being a god or a hero in any religion, and the Mayans gods are no exception. Man, made from earth (first try) and wood (second try), is finally (third try) given full animation from yellow and white corn, which transforms the beings into clever and respectful analogues of the gods themselves. At the center of the saga are mystical and ritual sacrifices, family genealogies, and especially the adventures of the Hero Twins, Hunaphú and Xbalanqué. These two child tricksters eventually defeat the wicked underworld gods and ascend into the heavens as the Sun and the Moon, where their beneficial cooperation makes possible the continued planting of corn and the cycles of the seasons, thereby assuring the future of man.

In the final panel of the exhibition the god Tohil is shown receiving blood sacrifices from his human subjects. In return for this offering Tohil’s fiery breath ignites a torch, which is then given to the people. The image of the overwhelming power and mystery of this giant god and his gift of fire, is one of the highlights in Rivera’s poetic and simple illustrations of Popol Vuh.